The Long Road to the 2010 Constitution: A Forty-Year Struggle

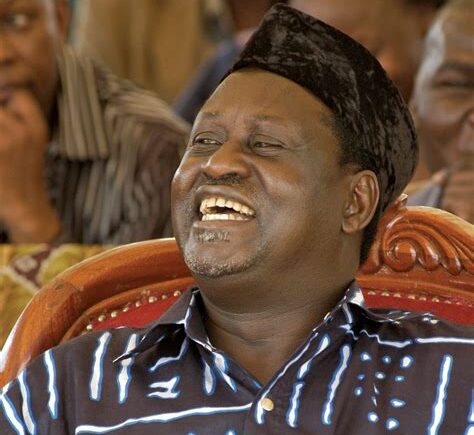

If any single achievement defines Raila Odinga’s legacy, it is the 2010 Constitution of Kenya, a document that fundamentally transformed the country’s governance structure and expanded citizens’ rights.

But this triumph was not the work of a single moment; it was the culmination of decades of struggle, sacrifice, betrayal, and persistence.

Raila’s commitment to constitutional reform began in the early 1990s when he joined the fight to repeal Section 2A, which had made Kenya a one-party state. Even after multiparty democracy was restored in 1991, Raila understood that without deeper constitutional changes, Kenya would remain trapped in a system that concentrated power in an “imperial presidency” with few checks and balances.

The Bomas of Kenya Process: Hope and Betrayal (2001-2005)

When the NARC coalition won the 2002 election, ending KANU’s 39-year rule, Raila believed the time had finally come for comprehensive constitutional reform. Kenyans had been promised a new constitution within 100 days of the NARC government taking office. President Kibaki himself had made constitutional reform a cornerstone of his campaign.

In 2001, Parliament passed the Constitution of Kenya Review Act, establishing the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC) chaired by Professor Yash Pal Ghai. The CKRC embarked on a historic “people-driven” process that collected views from Kenyans across the country. The culmination of this exercise was the Bomas of Kenya National Constitutional Conference, which brought together delegates from all walks of life to debate and draft a new constitution.

The Bomas Draft that emerged was progressive and bold. It proposed:

- A semi-presidential system with an executive Prime Minister as head of government and a ceremonial President as head of state

- Devolution of power to regional and local governments

- Significant reduction of presidential powers

- A strengthened Parliament and independent judiciary

- Expanded Bill of Rights

- Equitable distribution of resources

But the Bomas process was not without the shedding of Luo blood. On September 14, 2003, three gunmen stormed the home of Dr. Crispin Odhiambo Mbai, the University of Nairobi scholar who chaired the Devolution Subcommittee at the Bomas Constitutional Conference. They shot him three times around 3pm along Ngong Road. He died while being treated at Nairobi Hospital. The gunmen took nothing, this was clearly an assassination, not a robbery.

Dr. Mbai was not just any delegate. He was considered one of Raila’s key allies and one of the few scholars who could articulate and deliver a practical framework for devolution, the very concept that threatened the centralized power structure that Mount Kenya’s political elite had enjoyed till then. His assassination was not just the killing of a scholar; it was an attack on the constitutional review process itself.

Initial speculation linked Dr. Mbai’s death to political forces, elements within government or among those opposed to devolution who wanted to derail the constitutional process. Twenty-two years later, his killers have never faced justice. His death remains one of the darkest stains on Kenya’s constitutional journey and a reminder of the price some paid so that Kenya could have the 2010 Constitution.

Raila and his allies pushed forward despite this tragedy, knowing that to retreat would be to dishonour Dr. Mbai’s sacrifice and abandon the dreams of millions of Kenyans.

Raila and his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) faction within NARC strongly supported the Bomas Draft. They saw it as the fulfilment of the promise to fundamentally transform Kenya’s governance. But President Kibaki and his inner circle, particularly ministers from the Mount Kenya region, were deeply opposed to the devolution of presidential power.

As the Bomas process neared completion in 2004, Kibaki’s faction began to sabotage it. They removed Professor Yash Pal Ghai from leadership and handed the draft to Attorney General Amos Wako, who significantly altered it. The resulting “Wako Draft” (also called the “Kilifi Draft”) retained most presidential powers, weakened devolution, and essentially preserved the status quo that had allowed presidents to rule with minimal oversight.

Raila was livid. He saw the Wako Draft as a betrayal of everything Kenyans had fought for. When Kibaki insisted on taking the Wako Draft to a referendum in November 2005, Raila made a fateful decision: he would lead the campaign to defeat it.

The 2005 Referendum: Orange Revolution

The 2005 constitutional referendum became one of the most divisive moments in Kenya’s post-independence history. The ballot featured two symbols: a banana for “Yes” (supporting the Wako Draft) and an orange for “No” (rejecting it).

President Kibaki, his Vice President Moody Awori, and much of the government machinery backed the banana. Raila Odinga, leading the “Orange” campaign, was joined by an unlikely coalition that included his father’s old rival, former President Daniel arap Moi, and KANU politicians who saw an opportunity to weaken Kibaki.

The referendum campaigns were bitter and personal. Kibaki’s side accused Raila of working with Moi to undermine reform. Raila countered that the Wako Draft was a sham designed to perpetuate dictatorship. Rallies turned violent. The country was polarized.

On November 21, 2005, Kenyans voted decisively: 58% rejected the Wako Draft. Raila’s Orange campaign won overwhelmingly in Nyanza, Western Kenya, the Rift Valley, and the Coast. Even in some parts of Central Kenya, turnout was suspiciously low, suggesting that Kibaki’s own base was unenthusiastic about his constitution. It was a stunning defeat for a sitting president.

In retaliation, Kibaki immediately dismissed all ministers associated with Raila from the cabinet, including Raila himself as Minister for Roads. But Raila had won something more valuable than a cabinet position: he had stopped a flawed constitution, proven his political strength, and earned a symbol, the orange, that would become the rallying cry for his next political movement.

From the ashes of the 2005 referendum, Raila formed the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), which would carry him into the fateful 2007 election.

Published by the Luo National Congress

October 17, 2025